High Holborn Pit

(Butterley Park No.5 Colliery)

The High Holborn woods at the bottom of Alfreton road Codnor are planted on the old pit hills created by High Holborn Colliery, also known as Butterley Park No. 5 pit.

In the early 1970s the pit shaft still existed and before it was capped with concrete, it was possible to climb up the protective stonewall and see down the shaft, which still contained the wooden guide rails for the cages.

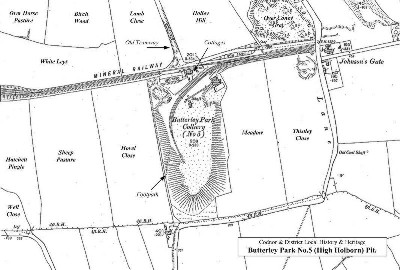

Fig.1 This Map from 1901 shows the Butterley No.5 Colliery (High Holborn)

and mineral railway, which is now the embankment at the back of Codnor

Industrial Estate. Previous to this mineral railway the coal was transported on a horse drawn tramway to the Cromford Canal and Codnor Park Ironworks. I have named the fields that I know and I can also confirm that the field that is now covered by the spoil heap was called "New Laid Down".

Note the position of the old cottages and also the miner’s path leading up the pit hill. The same path still exists today.

In 1972 the Ripley & Heanor News interviewed 87-year-old Tom Langton who was thought to be the only man still living who had worked down High Holborn pit.

He started work at High Holborn pit when he was 15 years old. He described the coal has being hand-got using the stall method. His only light came from candles provided by the “Candle Martin” who lived on Heanor Road.

The pit had three seams worked by a total of fifty men and boys, a soft coal seam at 150 yards; the hard coal seam was a further 18 yards deeper and also an Iron stone seam that was worked by JimWhysall.

He remembers before the men would go down the pit in the morning, they would watch for the wagon train coming past the forty Horse pit along the embankment, and count the number of wagons. Sometimes there were only two wagons to fill, so they knew they only had to work a quarter of a shift, four wagons would mean half a shift and eight or nine a full shift would be required.

Each wagon would hold ten tons of coal so the High Holborn pit was capable of producing approximately eighty tons of coal per day.

Tom recalls that three days a week after his usual day shift of 6am to 3pm, he would return to work at 9pm with another lad, Alf Lamb, and empty water into barrels, which were then taken by trucks and emptied into a sump in the pit bottom and channelled through culverts to the pumping shaft at Butterley park. His shift would finish at 2am when he would go home and grab a couple of hours sleep before returning to work the next day.

The pit gaffer at the time was Tom Brown who lived on Heanor Road. Tom Langtons uncle, William Langton lived in one of the three cottages in front of the pit.

Fig.2 This picture of High Holborn cottages was probably taken in the

1970s, not long before they were demolished.

Displayed Courtesy of the wood Collection,

http://www.picturethepast.org.uk/

William was the engine-wright for the company, but was unfortunately killed whilst repairing the old beam engine at Butterley Park.

Williams’s son Joseph Langton sold pianos, His adverts would appear in the Ripley & Heanor News giving his address as High Holborn, Codnor.

Fig.3 Left; Newspaper advertisement dated 1889 for Joseph Langton's Pianos and Organs, High Holborn Codnor.

Displayed courtesy of The Ripley & Heanor News

Right; A typical Estey Organ from 1889 as seen in Joseph Langton's advertisement.

High Holborn pit was closed in 1909 due to flooding; it was not possible to rescue any of the ponies still down the pit.

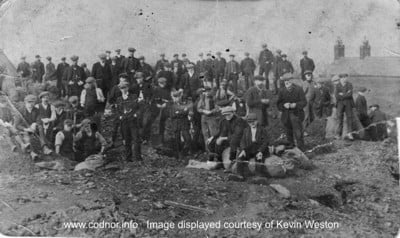

Fig.4 This picture shows miners picking coal from the High Holborn pit

banks during the miner’s strike of 1911 – 1912.

Fig.5 This picture is taken from the same position as Fig.3 but panned a little further to the right so you can see the High Holborn cottages in the background. The man standing in the foreground with his pocket watch chain hanging from the front of his waistcoat is Herbert Weston, born in Codnor in 1884.

The Childrens Employment Commision of 1842

A report by John Michael Fellows ESQ.

BUTTERLEY PARK, HIGH HOLBORN IRON-PITS. (Butterley Company.)

No.196. Thomas Hunt, engineman.

The engine is 20 horse power and it works Nos.5 and 6 shafts, pumps and works the railways.

No.5 is 160 yards deep. The waggons are drawn by ponies and boys, three or four under 13 draw by the belt. They are let down at six or seven with three quarters of an hour allowed for dinner.

Half days are from six to two with no dinnertime allowed. The shaft is not laid in lime and there is no bonnet. There is a Davy lamp in the office about a mile off. The pit is winded on the banks of two coal pits. Where they are working ironstone it is only 132 yards deep. They are not working the coal at present.

The Butterley Company never work their shafts with chains and four to six are let up or down at a time. About two months since Joseph Waters broke his arm by the bind falling. There is very little wildfire or blackdamp in Nos.5 or 6.

No.5 is pretty well guarded when not at work by the cover-fixing close over.

The shaft has a metal rim. It is wet in the shaft and the banks are up to the calves in sludge and water.

There are three banks and they are from 100 to 150 yards long. The waggon road is 120 yards with a headroom of 5 feet. The cabin is very small and merely of loose stones.

Fig.6 Remains of old boilers abandoned at the side of the spoil heap

Nottinghamshire Guardian 3rd June 1899

The Fatal Colliery Accident At Codnor

The inquest on the body of John James Needham was held by Mr. Harvey Whiston the District Coroner at the Glass House Inn on Monday evening.

Bertha Needham said the body was that of her husband, a collier aged 24. He went out of the house at twenty minutes to six on Friday morning to work at No. 5 Colliery High Holborn. She heard of the accident on Friday afternoon. He was brought home dead at about four o’clock.

Thomas Watley of Mill Lane , Codnor, collier working at No.5 pit, deposed to working with Needham on Friday last. In the afternoon witness was “holing” and thought Needham was at the other end of the stall, where he had been during the day. He heard something drop and shouted “are you right Jack?” The sound was not far off. Getting no answer, he went to the end, but could not see deceased, but heard him make a noise and went to where he was. He found him with his head fast under some rock which had fallen. The piece was too large for him to lift, and he shouted for help to his father and James Searson. They were two or three yards down the gate and about ten yards from where the fall had taken place. All three tried to get deceased out, but failed to shift the rock. They got more help, It took about ten of then to move the rock, When they got him out he was not dead. It was about twenty minutes from the fall until they released him. Plenty of timber had been set in the stall, the deputy having been through a little before.

In answer to Mr Hewitt, witness said supports had been properly put from the coal to the roof.

James Searson, collier gave evidence as to having heard a shot in the gate ten minutes before the accident. The shot might have shaken the roof.

Henry Marshall, deputy, deposed to examining the stall on the afternoon in question at two o’clock and found everything safe and still. He fired a shot and waited about ten minutes, but it did not disturb the roof.

A verdict of “Accidental death” was returned.

Information for this page was obtained from the following sources.

The Heritage of Codnor & Loscoe, by Fred S Thorpe 1990

The Coal Mining History Resource Centre, Picks Publishing & Ian Winstanley

A History of Mining in the Heanor Area, Heanor & District Local History Society publication 1993

Life in Old Heanor, Heanor & District Local History Society publication 1983

Ripley & Heanor News, January 21st 1972

Nottinghamshire Guardian 3rd June 1899